One day, Tracy Dixon-Salazar’s daughter, Savannah, then 2, suddenly seemed like she was choking. Panicked, the family called 911 and paramedics informed them that Savannah had a seizure.

“Both my husband and I went at the same time, ‘What’s a seizure,’” Dixon-Salazar, 52, from San Diego, recalls to TODAY.com. “We actually went six months and she didn’t have any and then at the age of 3 they came back hard and fast. She started having hundreds of seizures a day.”

At the time, doctors hesitated to call them seizures and instead referred to them “episodes” or “spells.” Dixon-Salazar later learned Savannah had epilepsy, but doctors didn’t want to diagnose her with it because they feared stigmatizing her.

Frustrated with trying to comprehend why Savannah went from a seemingly health child to having intense and frequent seizures, Dixon-Salazar returned to school and earned her Ph.D., eventually uncovering a mechanism that, in part, explains why Savannah, now 30, experienced her seizures. It also led the family to a treatment that reduces the number of seizures Savannah has.

“I just wanted to understand what was going on with my child. I didn’t go into this thinking I was ever going to help her,” she says. “That was a surprise to me.”

‘I needed an outlet for the pain.'

After Savannah’s seizures became frequent and ongoing at 3, Dixon-Salazar and her husband took her to several doctors, who weren't always transparent about Savannah's diagnosis. What's more, testing never revealed why she would have seizures — there was no family history of them and Savannah never experienced a traumatic injury that could cause them.

“We actually found out she had epilepsy by reading her chart. No one ever told us,” Dixon-Salazar says. “I requested her medical records because I was a mom on a mission.”

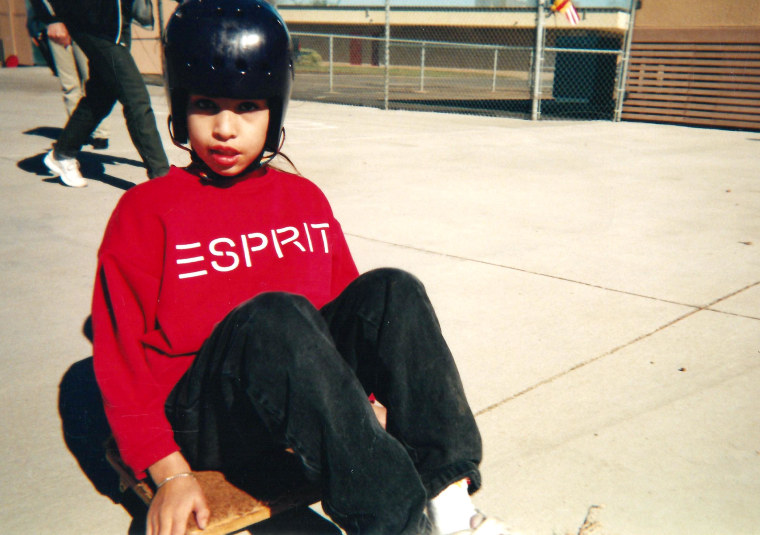

After almost two years of seizures, Savannah, then 5, developed Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), a condition that includes frequent seizures and developmental delays, according to the National Library of Medicine.

“No one’s born with LGS. LGS is something that develops over time when the brain is barraged by seizures,” Dixon-Salazar says. “Your brain is also trying to develop. She was 3 years old, and her brain was trying to put itself together … she’s got all this abnormal seizure electricity going on, so the brain wires itself wrong.”

According to the LGS Foundation people with LGS have four characteristics, which include:

- Early childhood seizures

- Treatment-resistant seizures and more than one type of seizure

- EEG test results that show abnormal brainwaves

- Intellectual disabilities or developmental delays

At the time, the family “had no idea what was going on,” and felt overwhelmed by Savannah's health troubles. While the diagnoses finally gave Dixon-Salazar a name for Savannah's condition, all the information she received seemed vastly different than what occurred in Savannah's life.

“The messaging (in the 1990s) was ‘You can live a full life with epilepsy,’” she recalls. “None of this was what we were experiencing at home. Savannah stopped developing. We’ve had to resuscitate her. She’s in the hospital all the time.”

With few answers, Dixon-Salazar realized she needed to become an expert in her daughter’s health.

“This disease, it comes into your life. It’s uninvited. It’s unannounced and it takes over every aspect of your daily life,” she says. “And who is more motivated to understand it than the people who are directly impacted? And plus it’s attacking the thing that is most precious to you — it’s your kid.”

As time went on, Savannah's seizures lessened but still she experienced hundreds of seizures a month and Dixon-Salazar estimates Savannah had 40,000 seizures in her life. At 3, she stopped developing. She never learned to use the bathroom, read or write. Mentally, she acted like a toddler even as she aged.

Sometimes Savannah had seizures that would not stop, Dixon-Salazar says, and they'd have to "intervene by either taking her to the emergency room or give her rescue meds.”

Rescue medications are often fast-acting benzodiazepines used to stop seizures, according to the Epilepsy Foundation. When Savannah was young, Dixon-Salazar had to administer them rectally but now there’s a nasal spray as well as pills that dissolve under the tongue.

Around this time, Dixon-Salazar decided to go to back to school. When she graduated from high school years prior, she went into the military. Now she was enrolled in college and took English classes in the hopes it would help her better understand the scientific literature she was reading. Soon, she started taking science classes and fell in love.

“I was just trying to understand how this kid, this healthy 2-year-old could go from being totally normal to having seizures and her life derailed. And reading those (medical studies) drove me to go to college,” she says. “I needed an outlet for the pain.”

Over 12 years, she earned an associate, bachelor and master’s degree before getting her Ph.D. in neurobiology and finishing a three-year post-doctoral program. School helped her feel less hopeless.

“I couldn’t help my daughter,” Dixon-Salazar says. “Studying was something I could do.”

For years, doctors didn’t understand what caused Savannah to have such severe epilepsy. At the time, they often said to Dixon-Salazar “thankfully we don’t need to know what causes epilepsy in order to treat it.”

Dixon-Salazar thought that “dogmatic way of thinking” was problematic and it drove her to study genetics. After she finished her post-doctoral training, she began working in a lab that was examining the genetics of epilepsy. Researchers would conduct genetic analysis of children and their families “to try to understand how genetic mutations were leading to the disease.” Dixon Salazar hoped she could learn something about her daughter’s illness and analyzed her genome.

“Savannah didn’t have an inherited epilepsy,” Dixon-Salazar explains. “I sequenced her. I did all this analysis, and I was able to show she’s got calcium channel mutations."

These mutations meant too much calcium was passing through these pathways and that caused Savannah's seizures. Dixon-Salazar found this interesting especially because the family had witnessed what calcium did to Savannah, hadn't realized the connection at the time. Over the years, Savannah took medications that leached calcium from her bones. To counteract this effect, doctors sometimes recommended that Savannah take calcium supplements. Each time Savannah took them, her epilepsy worsened.

“We tried (calcium) three different times and she always had more seizures,” she says. “I’m like ‘There’s something to this.’”

After this discovery, Dixon-Salazar eventually brought her findings to Savannah’s doctors. While the doctor was unfamiliar with the genetic findings, they agreed to put her on a calcium blocker, which is used for high blood pressures and arrhythmias.

“There’s actually a drug that blocks these exact calcium channels,” Dixon-Salazar says.

Very soon after, Dixon-Salazar noticed a change in Savannah.

“It worked within two weeks,” Dixon-Salazar says. “She went from having 300 seizures a month and going into these nonstop seizures a couple of times a week … to a 95% reduction in her seizures and it’s been 11 years, which is pretty incredible.”

Caregiving and advocacy

Since starting this medication, Savannah has been thriving. When she started taking it, she still functioned like a 3-year-old from “so much brain damage.” Today, things look different.

“She just exploded in her personality and her talking and her walking and her potty training and oh my gosh she is just so sassy,” Dixon-Salazar says.

Dixon-Salazar serves as the executive director of the LGS Foundation and has become outspoken about this condition and caregiving. UCB, a pharmaceutical company, released survey results looking at caregiving in the rare epilepsy community, which found only 22% believe they had access to resources long-term planning. For Dixon-Salazar finding support from loved ones helped her grapple with the difficulties of caregiving and she hopes others can find this, too.

Recently Dixon-Salazar and Savannah experienced a first in their relationship. While Dixon-Salazar was preparing to attend an event, Savannah came into the room.

“She asked if she could help. We picked out a dress and it was the first time in our lives that we did something normal as a mother and a daughter,” she says while crying. “It was pretty cool.”

Savannah now is “obsessed” with boys and listens to singer songwriters on social media. While she enjoys puzzles, she cannot work because she doesn’t read or write. She’s very trusting “so she’s at risk of being taken advantage of,” Dixon-Salazar says.

“We’ve tried to find a place for her in this world,” she says. “We’ve been asked not to participate.”

Dixon-Salazar says it feels like her daughter is too much for others because of the number of seizures and the severity of her intellectual disability. It’s devastating for Dixon-Salazar but that keeps her motivated to speak up.

“Everything’s hard. I can’t even go to the neurology office with this kid. I spend a lot of time fighting with insurance companies,” she says. Still, Dixon-Salazar is determined to leave the world better than she found it, and advocacy, she says, is the way to do it. Her daughter and those like her are dealing with a difficult disease, but there's room for them here and she's wants the world to know that.